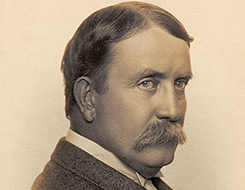

On a recent speaking trip to Chicago I finally saw the opportunity to undertake a pilgrimage I had been planning for over a year. I’ve long been a fan of Daniel Hudson Burnham, the man who envisioned, built and operated the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, one of the most jaw-dropping achievements of the latter part of the 19th century. The fair that year was called “The Columbian Exposition” to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ landing in the new world. Burnham’s commission was to outshine the Paris World’s Fair which four years earlier had featured the unveiling of the Eiffel Tower. (Click on any photo for a better look. Most will enlarge.)

The Chicago City Council chose to locate the fair in South Park (now known as Jackson Park), a swamp on the shore of Lake Michigan 8 miles southeast of the Windy City. The famed landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted (who designed New York’s Central Park and the grounds of the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina) quipped that it would be difficult to find a worse place to hold the exposition. But the project moved forward anyway.

OUT DISNEY-ING DISNEY

The fair would soon blanket 600 acres between 67th Street on the south and 56th street on the north, plus a horizontal strip of parkland which today bisects the University of Chicago. By comparison, Disneyland™ (the one in California), The Magic Kingdom™ (Orlando), EPCOT™, and Hong Kong Disneyland combined would all fit within her borders. In three short years, Burnham conceived and oversaw the transformation of that useless bog into a fantasyland dubbed “The White City”, interlaced with canals,

arched bridges, sculptures, exhibits and fountains. He led 40,000 workers in the design and construction of nearly 200 palatial edifices, 5 of which were among the 7 biggest buildings in world history at the time. The Great Pyramid of Giza could easily fit inside the largest, which could hold 300,000 people. Their splendor is said to have caused first-time onlookers to gasp in wonder or even burst into tears, overwhelmed by their beauty and grandeur.

THE FAIR FEATURED:

- The first significant use of alternating current in history

- The first-ever widespread use of incandescent lighting

- The world’s first indoor ice skating rink

- The world’s first toboggan ride (over ice!)

- The world’s first public aquarium (it even contained a whale)

- The public release of Cream of Wheat, Wrigley’s Spearmint Gum, and Pabst Blue Ribbon Beer

- The first public viewing of an automobile

- A full-size Norwegian Viking ship

- A replica of Mount Vernon

- The (real) Liberty Bell

- A pomp-and-circumstance arrival on Lake Michigan by exact replicas of the Nina, the Pinta and the Santa Maria that had sailed all the way from Spain.

- The world’s first Ferris Wheel, which carried an astounding 2,160 passengers, almost double the capacity of today’s world’s-largest in Las Vegas, “The High Roller”

The Ferris wheel was placed in a portion of the park named “Midway Plaisance” (literally, “central place for boating” because of earlier plans for a canal through that location that were eventually scrapped). For this reason, to this very day the part of a fair dedicated to carnival rides is called a midway. The photo below of the midway was probably taken from atop that Ferris wheel.

The fair hosted 27 million people during its 5-month run, a figure made even more astounding when one takes into account that it occurred before the availability of car or plane travel. This number includes a whopping 751,026 paying guests on a single day, October 9, 1893. Disney’s Magic Kingdom™, by contrast, receives 19 million visitors in an entire year, with a single day highest-attendance-ever of about 90,000.

GONE WITH THE WIND

Sadly, there is almost no physical evidence at the site today that the fair ever existed. I wandered Jackson Park for an hour looking for any historical markers, plaques, or even land or water features that might match one the many photos or maps I’d studied. Most of the area is now covered with ball fields, a golf course and marinas. Some of it has reverted to wild, inhospitable marsh. Only one building remains, the onetime Art Building that now serves as Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry at the extreme north end of the park. My trip to the once-impressive site left me stunned that I could find only one tiny marker indicating that the amazing event had taken place at all.

A replica of The Republic statue (left) that once towered as the fair’s iconic centerpiece on a pedestal in the “Great Basin” (right) stands today in a traffic circle as the lone reminder of the majesty that once was. This is a photo of the original sculpture’s back, facing the domed Administration Building that served as the main entrance to the fair. What remains of the Great Basin is now Jackson Park Inner Harbor where the wealthy park their yachts, a lowly boat ramp occupying the spot closest to where the gilded statue once stood. An ice skating rink now occupies the site of that archetypal Ferris wheel directly in front of the University of Chicago Law School. The entire fair (other than the one aforementioned surviving building) burned to the ground at the hands of a careless vagrant a few months after the fair closed, effectively erasing this historic celebration of human ingenuity from the collective consciousness. Below is a photo of what the site looked like by late 1894.

THE POWER OF A DREAM

After touring the former fairgrounds I made a second pilgrimage, this time to the graveside of Daniel Burnham tucked away on a tiny island in small pond in the farthest corner of Chicago’s massive Graceland Cemetery. There he lies buried alongside a few family members, sharing a relatively small nondescript tombstone with his wife, and no mention whatever of his achievements. My favorite quote from the once-famous but now-forgotten architect is this:

Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably themselves will not be realized. Make big plans; aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone be a living thing, asserting itself with ever-growing insistency.

Leadership involves making huge plans, because tiny plans inspire no one to action. Rather, they lull people into complacency or even put them to sleep. Big plans – and only big plans – will capture the hearts and imaginations of those around you and galvanize them to action.

September 8, 2015